|

SELECTED RECENT ARTICLES, REVIEWS & CATALOG ESSAYS

The

Paintings of Joseph Hughes: Icons of Color

Chris Ashley, Joseph Hughes: Selected Paintings

2005-2008

room for painting room for paper, San Francisco, 2008

Hughes

Paintings at Takada

Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle, September

16, 2006

Joseph

Hughes at Takada

Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle, October

30, 2004

Seeing

the Hovering Image: Joseph Hughes' Recent Paintings

Chris

Ashley, Look,

See, October 2004

Joseph

Hughes and Color Painting

George Lawson, Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002,

San Francisco, CA, 2002

The

Image of Color

James Lavino, Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002, San

Francisco, CA, 2002

|

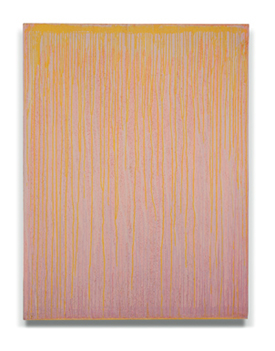

2008/

III (THALO GREEN)

Acrylic/ linen

20.5 x 16.5 in 50.5 x 41.5 cm

|

The Paintings of Joseph Hughes: Icons of Color

From

the catalog "Joseph Hughes: Selected Paintings

2005-2008," room for painting room for paper,

San Francisco, CA, 2008

It

is remarkable to observe that during the fifth decade of

his career Joseph Hughes, whose work has often been seen

in the context of Radical Color Painting, is still experimenting

and innovating. Yet, while assuming Color Painting's primary

concern for the integration of support, surface, medium,

pigment, and mark, Hughes' pursuit of a profoundly visual

experience of color, light, and space remains uniquely open.

Notably, his recent focus on emphatic gesture has resulted

in particularly vibrant and sensitive, beautiful and intelligent

paintings. It has also taken him into a new and exciting

area of discovery.

Hughes'

palette is consistently intense and diverse, often even

unusual. Thalo, Dioxazine, and Acra are powerful and luminous,

yet these staining colors are so difficult to work with

that most artists simply avoid them. But even when Hughes

uses the more common Ultramarine or Siena--and he has a

special way with white and gray--his color remains clear

and brilliant because his command of acrylic medium, used

in alternating glazed and opaque areas, lets him achieve

the jewel-like, lapidary qualities found, for example, in

Rembrandt, whom Hughes greatly admires.

Drawing is now more obviously important to Hughes in ways

rarely found in Color Painting, where instead it is usually

located at the edges of fields, shapes, and the canvas'

periphery. Against Hughes' downward-flowing colored grounds,

lines of paint are literally flung at the canvas; the presence

of the painter's body in making these paintings is clearly

evident. The pressure of thrown paint forces these lines

to subtly fray and splatter out and upward at their edges.

Across the painting's surface, arcs of color gracefully

run parallel, touch, or crisscross, forming variously sparse

or dense fields of interwoven lines.

On

the vertical plane of 2008/III (THALO GREEN), for example,

a few thin dark green lines sketch a basic scaffolding on

a medium green background, over which thicker skeins of

turquoise accumulate as a grove of tangled trunks. The opposing

directions of the downward-flowing background and the foreground

figures reaching up suggest movement and tension, like the

body's struggle to remain upright means resisting gravity's

pull. In this Hughes risks the associations that the figure-ground

dichotomy introduces and that Color Painting usually sidesteps,

which leads to confirming, wrestling with, and wrangling

painting's eternal dualities: abstraction and realism; window

and plane; illusion and surface; picture and object; reference

and thing.

Historically,

as pictures, symbols, and objects, painted icons encapsulate

these dualities, and are vehicles of emotion, belief, and

beauty. Joseph Hughes' paintings are personal icons for

believers in the transcendent experience of color and its

role in exploring the reaches of our psychological and spiritual

nature. They call for and support our discovery of self

via observation, conjecture, intuition, and reason. In experiencing

these paintings we find an ideal, an archetype for a way

to look, think, and feel.

Chris

Ashley

Oakland , California

September 2008

|

|

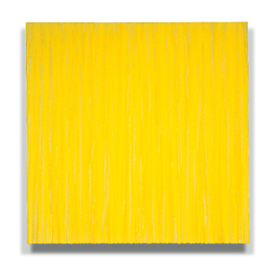

2006/ IV (GREY-WHITE)

Acrylic/linen

18 x 17.5 in 46 x 44 cm

(Private Collection)

|

Hughes Paintings at Takada

Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle

September 16, 2006

Like

all abstract painters today, Joseph Hughes risks appearing

withdrawn and self-involved in a world on fire. Events have

made people wary of the idealism that abstract painting

once seemed capable of objectifying by exempting itself

from society's traffic in symbols and whimsies. Today's

contending winds of ideological fervor form a climate even

more dully hostile to abstraction than that of good old-fashioned

philistine dismissal.

Hughes'

recent work at Takada still shuns reference, but its austerity

makes room for sour, abrasive sensations in which we recognize

all too readily the texture of everyday consciousness.

Hughes

has slowly loosened his approach in recent years. Faintly

modulated color fields achieved by pouring acrylic have

given way to an inscrutable combination of pouring and brushwork.

In a picture such as "2006/IV (GREY-WHITE)," the

technique produces a thicket of bristled striations that

snags the eye like visual Velcro. Not a pleasing sensation

at first, but surrender to it and the painting, like most

of the others on view, will unfold absorbing ambiguities

of color and space.

Peeling

apart the details of Hughes' work slowly turns into a process

of separating the strands of visual awareness, disentangling

those spun by words from those not.

|

|

2003/

IV (THALO DIOXAZINE)

Acrylic/ canvas

25 x 22 in 64 x 56 cm

(Private Collection)

|

Joseph Hughes at Takada

Kenneth Baker, San Francisco Chronicle

October 30, 2004

Joseph

Hughes at Takada: Even amid the blare, haste and bluntness

of big media, painting and the other static arts remind

us what significant differences small adjustments can make.

The recent work of San Francisco painter Joseph Hughes,

whose show at Takada ends today, proves the point.

For

years Hughes has made monochrome abstractions by pouring

acrylic over stretched canvases. The smooth sheets of color

that resulted, some with drips trailing at their bottom

edges, achieve a soothing objectivity but at a cost of the

internal energy that abstraction requires to compel attention.

Hughes

continues to work by pouring liquid pigment, lighter hues

over darker grounds, but he has lately taken to guiding

the pours with small brushes. In "2003/ IV (THALO DIOXAZINE)"

the technique has yielded a surface thatched with striations

of color. The marks appear to dance without Hughes' hand

making them do it.

Knowing

his technique takes nothing away from the impression it

creates of paint caught raining down in some parallel climate,

a domain that mirrors our own without imitation, much as

the painter's consciousness does.

Hughes

seems to have worked for years on the threshold of this

discovery. It has finally injected his painting with the

liveliness of expressionism, minus its inevitable hint of

self-indulgence.

|

|

2004/III

(JENKINS GREEN)

Acrylic/ canvas

60 x 56 in 152 x 142 cm

(Private Collection, Tokyo)

2004/II

(THALO DIOXAZINE)

Acrylic/ canvas

18.5 x 17.5 in 46 x 43 cm

(Bergner+

Job Galerie, Mainz, Germany)

2001/

I (CADMIUM RED)

Acrylic/ canvas

48.5 x 41 in 123 x 104 cm

2001/

IV (JENKINS GREEN)

Acrylic/ canvas

18.5 x 17.5 in 47 x 45 cm

2001/

II (HANSA YELLOW)

Acrylic/ canvas

36 x 31 in 92 x 79 cm

|

Seeing the Hovering Image:

Joseph Hughes' Recent Paintings

Chris

Ashley, Look,

See, October 2004

Introduction

Joseph Hughes is showing six paintings at the Takada Gallery

in SF. All are vertical, stout rectangles. Five paintings

are in the eighteen to twenty inch high range, and one painting,

by far the largest, reaches sixty inches in height. All

are painted in acrylic; four, including the large painting,

are on canvas and the final two paintings are on linen.

Walking

in the gallery one initially appears to be confronted with

six monochrome paintings, each a different color, but if

one spends just a little time with the paintings one finds

that there is much more going on here than that. To describe

the making of these paintings in terms that sound like a

system or method is not to say that the paintings are either

systematically or methodically made with a predictable outcome,

that they are all the same but just use different colors;

it simply means that the artist does employ a process that

can be described, and that the paintings are individuals

in a family of work exploring a set of problems on which

the artist is for now focusing.

Shape

& Drawing

Hughes' stretchers are actually trapezoids. The top and

bottom edges are parallel, but the top is slightly wider

than the bottom, which helps the eye make a visual correction

so that the stretcher appears to be square. It isn't something

immediately noticeable, but if you look close enough you'll

wonder if the rectangles are actually square. I thought

I saw that the paintings were not square rectangles and

asked Hughes about this, which he verified.

Most

painters today don't do this, though it's not an uncommon

technique among painters very concerned about the painting

as an object and a perceptual experience. Go back four hundred

years or more to look at, for example, paintings made for

a particular wall high above the viewer in a church; the

height at which the painting is hung requires the viewer

to look up at the painting, thus forcing a foreshortened

view of the painting, meaning that the painting appears

to narrow the higher it gets. If instead the painting is

actually physically wider a certain amount at the top it

will appear to flatten out to the viewer's eye, preserving

the appearance of a square rectangle. The higher the painting,

and the larger it is, the wider it may be along the top

edge. Various tricks like this can be employed to influence

the viewers perception of the work.

If

one doesn't look close enough at the painting to notice

its actual shape then it's easy to accept that it is actually

square, which is how perception works. It's an illusion.

One could call it realism, in the sense of the commonly

accepted use of the word in art: making something appear

real or natural through illusionistic means. That's just

one little argument in the many I could make that abstract

painting is actually realism. It is physical and perceptual,

it is an actual viewing experience itself as well as associative,

provoking feelings within the viewer that are in the moment,

not abstracted or in reaction to a depiction of experience

or feeling. But that's another essay.

Think

of these trapezoids, a means of perceptual correction, even

coercion, as the second piece of drawing the artist undertakes

in making each work. Yes, it is drawing, because it is specifying

a shape: it is a border, a line around what happens inside

the painting and the environment that contains it, and it

is illusory. But actually, the first piece of drawing is

the size of the stretcher, because the size of the stretcher

is a factor in the amount of correction required, determining

the angles of the trapezoid needed to force paintings of

different sizes to read as square. (How is this done? I

don't know; there must be some formula, but I've never done

it myself. That's a little research project.) And speaking

of drawing, and having mentioned how high a painting is

hung, there is a final piece of drawing in making the painting,

typically considered after the actual painting phase of

making the work, which is how high the painting, if it isn't

site-specific, is hung on the wall. I've just described

several drawing decisions to be considered even though a

pencil or brush hasn't even necessarily touched the surface

of the painting yet.

Painting

The actual painting phase in Hughes' process for this group

of paintings requires, as I understand it, basically four

steps after the canvas or linen support is secured over

the stretcher. All painting takes place while the stretcher

is hanging on a wall.

- First,

the surface is covered evenly by a rolled-on colored acrylic

ground; in the series this ground may appear to black,

although it is actually a mixed color.

- When

the first ground is dry another layer of acrylic is applied

over the entire surface. This ground may have some small

amount of acrylic mixed in, but remains transparent. Essentially,

Hughes is using a glaze technique.

- After

the second acrylic layer dries a prepared brush is used

to paint vertical and slightly diagonal strokes of more

fully pigmented acrylic. The prepared brush is a wide,

flat brush modified by cutting out sections of the bristles

to create gaps so that the brush no longer paints an even,

solid stroke. Imagine the original brush like the fingers

on a hand, straight and touching sides, forming a solid

surface. Now imagine spreading the fingers out so that

there are gaps between the fingers. The prepared brush,

like spread fingers, will not paint a solid stroke. This

is yet another drawing decision Hughes makes: he creates

and uses a brush that paints several roughly parallel

and separate smaller brushstrokes at once. In addition,

he attaches the brush to longer handles, from two to six

feet long, so that the brush isn't immediately held in

his hand but is extended several feet from his body, transforming

the act of painting from mere wrist or elbow movement

through his arm and shoulder into the rest of the body.

- After

the stroked colored paint is dry a final coat of lightly

pigmented acrylic is poured over the painting.

The

general approach undertaken at each stage of the painting

is one of allover-- the entire canvas is the area of attack

during each step, beginning with the design of the stretcher,

through the gestural painting, to the final pouring of clear

acrylic. At each stage Hughes is dealing with the entire

surface as a flat field to be filled, marked, or covered.

In the end the painting is a self-contained unit, a single

body comprising several layer, each layer a series of gestures,

smooth or gestural, designed to span and fit the complete

surface. The viewer sees the painting in at least three

modes: as a painted, gestural, flat image fitted over the

surface; as illusionistic light and space through color

and drawing; and as a single object composed of combined

materials integrally locked together.

Subject

& Color

The gestural component of each painting is probably most

easily taken to be the subject of the paintings, and at

least the most immediate level they are, if one thinks that

a painting has to present a figure, or depict an object,

or wear some kind of decoration, and that any of these is

necessarily the subject of the painting. The gesture can

be read as figure, object, or decoration, as a thing that

exists in an environment or on top of a surface. But there

are other components of the painting at work, and the reading

of the gesture as a figure is just one of these components

working in tandem with the others.

The

gesture is dependent on the black, a very uncommon color

over which to paint--putting aside paintings on velvet--as

it tends to kill color primarily because it does not reflect

light back through the color on top to the eye. The two

layers of poured acrylic, however, are a layer through which

light does pass, and these clear layers give each painting

a kind of buoyancy, as if the colored gesture is hovering

ever so slightly. The bottom layer of clear acrylic separates

the gesture from the black ground, and the top layer of

acrylic seals-in the gesture, containing it under a clear

surface and fixing it within the painting. This shallow

space over the gesture wraps the painting up, integrates

its components, and makes it a single object. But these

two planes of clear acrylic do something very subtle and

surprising, something even barely noticeable: the colored

gesture is suspended, floats between two clear sheets, like

a leaf in a book, an insect in amber, or moisture in a double-paned

window, and perhaps even more powerfully: like an image

in a mirror or a window. It is an image not quite there,

faint and hard to hold. The gesture is a record of the artist's

hand, suspended in a strange light in just that moment,

and suddenly the painting has incredible depth, while still

remaining very much a solid object.

The

gesture as an image resembles a flash, a stroke like a small

explosion, a flower underfolding, an action in the moment.

And yet each gesture is a flash as in an idea,

like a sudden thought--something flashed in my head,

or flashed before my eyes-- and is the manifestation

of this idea or thought in an action. The gesture is the

least mechanical and least programmed component of each

painting. As thin, quickly applied, streaky paint , held

between two sheets of acrylic, hovering over a dark background

providing minimal reflected light, the colored gesture is

almost a glimpse, like something fleeting, but of course

is also something static that can be returned to over and

over. With this in mind it may not only be that the gesture

is the primary image of the painting, but that the entire

constructed painting as a fleeting image--black, two layers

of clear acrylic, and a suspended colored gesture--is the

primary image: it's not a literally a mirror or window acting

as a fleeting image, nor is it the painted illusion of a

mirror or a window, but instead is a construction that enables

the experience of looking at and for a fleeting image. I'd

like to suggest that this viewing experience is a primary

subject matter of the paintings, and that possible meanings

to be found in these paintings include: the act of looking

for something; the act of trying to isolate this something;

the act of seeing something closely; the act of trying to

visually hold on to this something; the act of taking time

for looking; and the act of losing sight of something. That

the gesture is barely a something, is almost a nothing,

allows the viewer to look in a way that emphasizes the experience

and the recognition of this experience, not the recognition

of a specific object, place, or person, which would make

the painting a picture of something rather than something

in itself.

The

poet Jim Harris helps to illustrate this idea of looking

and recognition as a flash by identifying"the many

Japanese Haiku poets who make use of the lightning flash

as an initiating event (and metaphor) for a complete and

fleeting instant of sudden perception[1]." These poems,

all translations by Robert Hass, also connect to the ways

I've attempted to delineate of experiencing the marks and

imagery in Hughes' paintings::

How

admirable!// to see lightning and not think// life is fleeting.

-- Basho

Lightning

flash--// what I thought were faces// are plumes of pampas

grass. -- Basho

A

dry riverbed// glimpsed// by lightning. -- Issa

Harris

provides a final Haiku which frames "an act of layered

perception with the strobe of a glimpse, which seems analogous

to... the end-product... of Hughes' method" I describe

above as a suspended, just-caught image:

Calligraphy

of geese// against the sky--// the moon seals it. -- Buson

In

this recent body of Hughes' work, however, there is an exception.

In the smaller paintings the colored gestures barely cohere

into something more than a slight spray, fan, or web-- the

flash--which makes them better able to integrate into a

painted object. The largest painting is quite a different

story. It is covered and filled with a density of strokes

that are roughly the same size as those in the smaller paintings.

Where the smaller paintings more easily navigate the image/object

dichotomy, the larger painting, filled with overlapping

strokes, so much more readily reads as a picture. By this

I mean something more than the obvious ways in which the

many clustered strokes can begin to look like blades of

grass, a field, falling or spraying water, or crystals,

though they can do that, too. I mean that these bundles

of strokes cluster into shifting angles and form what might

conveniently be called a cubist kind of space: twisting,

sudden changes of directions, and overlapping. This space

is one which the viewer experiences and enters, moves within

and can find places to anchor to. The large painting, because

of its size and the accumulation of strokes, can't possible

provide the intimate experience that the smaller ones do.

It is a window onto a place with fixed spaces, and so is

a representation, a picture. In this respect the large painting

never becomes an integrated object.

Craft

& Presentation

Hughes' paintings are finely crafted. How they are made

is clear and consistent. I was most impressed by the bead

of acrylic that runs along and stops at all four edges of

the canvas as a kind of border. The evenness of surfaces,

the fine marks, and the clean edges of the canvas are evidence

of the great care with which these paintings have been produced.

These details are not small things; to be attuned to this

aspect is to find signs that point the way towards the value

of close looking, a way that, if followed, shows the viewer

that everything counts, that to not closely observe every

aspect of each painting is to miss the content and meaning

of the paintings. Hughes' conscious, intentional decisions

and process, made plain to the careful observer, and the

craft by which his decisions and process are carried out,

are indicators of the deeper purpose and content of his

work. His craft makes possible the joyful rewards from moments

of visual concentration and contemplation.

[1]

Excerpted from an email from Jim Harris to the author on

October 23, 2004.

|

|

2001/

VI (WHITE)

Acrylic/ canvas

36 x 31 in 92 x 79 cm

1999-2000/

I (HANSA YELLOW)

Acrylic/ canvas

26.5 x 21 in 67 x 53 cm

|

Joseph Hughes and Color Painting

George Lawson, Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002,

San Francisco, CA, 2002

During

the late 1970's and early 1980's I was painting in close

dialogue with a circle of artists in the Bay Area who were

exploring the range of experience available through the

material structuring of color. A seminal figure in that

group of artists was Joseph Hughes. His work, along with

our many discussions, left a profound impression upon me.

In

the intervening twenty-odd years, the "Color Painting"

movement has grown to include dozens of serious practitioners

all over the world, and many of the painters from that original

circle have gone on to gain national and international reputations.

While

the Color Painting movement now enjoys multinational attention,

it can claim substantial roots in the Bay Area, stemming

perhaps from the time Still and Rothko spent teaching here.

Anne Appleby, Joseph Marioni, and Phil Sims studied at the

San Francisco Art Institute. David Simpson and John Zurier

continue to work here, as did John Meyer before his untimely

death this year. From an art historical standpoint, Color

Painting belongs as much to our regional heritage as the

figuration of Park, Bischoff, and Diebenkorn.

From its inception in the Bay Area, Joseph Hughes has been

a key figure in the Color Painting movement. Working quietly

and steadily in his San Francisco studio, he has exerted

a strong influence on the Color genre.

Hughes

is an intelligent spokesperson, but more importantly, he

is also an intelligent painter. He has resolved, perhaps

better than anyone else working today, the dauntingly complex

relationship between the immaterial aura of color and the

physical support that generates the color image. This is

no small task. It is something on the order of resolving

the dichotomy between body and soul.

Moreover,

Hughes has won this resolution not through some stylistic

conceit or conceptual positioning, nor through any strategy,

but rather though the inherently slow process of maturation.

Hughes's genuine accomplishment is due in part to the knowledge

of painting he has acquired over the years, and in part

to his accumulated wisdom about the fluid nature of color.

Considered physically, Hughes' painting keeps the color

superbly grounded to the surface of the canvas; considered

metaphysically, his painting assures us with equal credibility

that color resides in an immaterial realm.

This

exhibition, a survey of Joseph Hughes's paintings from the

past thirty years, gives us a unique and welcome opportunity

to experience his work in fullness, and to enjoy the rewards

of his remarkable achievement.

San

Francisco, 2002

|

|

1973/

A6 (YELLOW RISING),

Acrylic/ canvas

62.5 x 47.5 in 156 x 121 cm

1987/

III (DARK BLUE VIOLET)

Acrylic/ canvas

72 x 72 in 183 x 183 cm

1989/

IV (RED VIOLET)

Acrylic/ canvas

76 x 76 in 193 x 193 cm

1990/

I (CADMIUM YELLOW)

Acrylic/ canvas

36 x 36 in 92 x 92 cm

1994/

IV (HOOKERS GREEN)

Acrylic/ canvas

50 x 49 in 127 x 125 cm

1999/

IV (THALO DIOXAZINE)

Acrylic/ canvas

26 x 24 in 66 x 61 cm

(Private Collection)

2001/

I (CADMIUM RED)

Acrylic/ canvas

48.5 x 41 in 123 x 104 cm

|

The

Image of Color

James Lavino, Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002,

San Francisco, CA, 2002

For

thirty years, through a continuous refinement and adjustment

of his painting process, Joseph Hughes has been engaged

in a single adventurous pursuit: an exploration of the physical,

psychological, and spiritual content of color. Throughout

these decades, Hughes has remained focused on distilling

the act of painting to its fundamental essence. His quest

is to realize paintings that are free from the bounds of

representation, free from the struggle of the ego, yet articulate

their full expression as actualized images of color

Hughes

came to color abstraction as a young painter in the 1960s

through his study of the heroic figures of the New York

School, notably Rothko, Pollock, and Kline. His indebtedness

to those painters is reflected in his lyrical abstract paintings

of the time, which made subtle references to landscape in

horizontal compositions of stratified passages of color.

As

his composition became more individuated and his involvement

with color deepened, Hughes came to understand that his

true subject matter was color itself. He therefore began

to eliminate all representational references from his work

and to focus exclusively on developing each painting into

a unique image of color. As a result, each painting reveals

itself as a kind of ideal presentation of its essential

color, with all elements of the painting- size, shape, color,

and format- in harmonious support of the color image.

By

1972, all of these elements were at work in Hughes' paintings.

For example, he began to emphasize the "objectness"

of the paintings by altering the edge of each work's support.

More extroverted works were made wider at the edge in order

to project more from the wall and therefore have a more

assertive presence. Hughes also changed his painting process,

eliminating the stratified color passages that had characterized

his earlier work. Instead, he filled nearly the entire field

of the canvas with layered glazes of complementary colors.

The basic color of each glaze feathers out at the edge of

the composition, giving the work a kind of optical frame

that causes the eye to search for the individual color of

each glaze without the multi-layered context of the body

of the painting.

In

order to involve the entire compositional field more actively

in the color structure of the painting, Hughes began to

investigate the technique of pouring the paint to animate

each glaze as it was applied. In the 1973 painting 1973/

A6 (YELLOW RISING), for example, we can see how the

pouring activates the structure of the color, adding a sense

of resolute and perpetual motion to the work. At the same

time, below the energy of the painting's active surface,

there lies a quiet richness and subtlety of color. This

unique relationship between surface and depth, between movement

and stillness, has remained a constant in Hughes's work.

In

the paintings of the late 1970s and 1980s there is a stronger

sense of gesture in the work. Hughes returned to the brush

as his primary painting tool, using brushes specially prepared

to give him a wide range of gestural possibilities. Generally,

these were large, rough horsehair brushes, mounted on long

poles that enable him to keep the entire painting in view

as he brushed with strong vertical strokes. The roughness

of the brushes worked each pigment into filaments that,

mingling optically with the other colors, created the impression

of a new, single composite color.

The

visual effect of these paintings is striking. Each painting

at first appears to be monochromatic, but as the viewer

contemplates the painting further, the "single color"

is revealed to contain a multitude of hues. Suddenly stark

differences in color are visible, and it becomes clear that

the apparently monochromatic image is in fact made up of

many separate interweaving colors. As we can see in 1987/

III (DARK BLUE-VIOLET), the single color image projects

the richness of its many complementary colors, much as a

"green" water lily painting by Monet projects

the richness of the distinct blues, violets, and yellows

of which it is composed.

In

the paintings at the end of the 1980s, such as 1989/IV

(RED VIOLET), there is a greater sense of fluidity

in the brushwork. One senses a stronger acknowledgement

of paint as an inherently liquid medium. The paint has been

allowed to flow more naturally, with less articulation by

the brush, especially in the later applications, giving

the painting a looser, freer feeling.

This

enhanced involvement in the fluidity of the paint continued

to develop, and by the following year Hughes had come to

define paint as "liquid color." In order to explore

this notion more freely, he returned to pouring as his primary

painting technique. In the painting 1990/ I (CADMIUM

YELLOW), for example, the entire color structure is

defined by a series of poured glazes. In these paintings

generally the paint remains fairly solid at the top of the

canvas, but as each new glaze proceeds toward the bottom,

it gathers into rivulets, leaving areas of the previous

layers exposed.

There

is an overall shift during this period toward an emphasis

on the objectness of the paintings, as Hughes focused on

integrating each work's physical properties with its psychological

concerns. The supports of the paintings are shaped more

radically, so that the stretcher tapers toward the bottom

to complement the paint as it flows down the canvas. A spacer

has been added to the back of the support, enabling the

painting to assert itself as a defined object hanging on

the wall, rather than seeming to be an architectural detail.

And the back edge of the stretcher has been rounded, so

that visually the edge flows more easily toward the space

separating the painting from the wall.

During

this period, too, Hughes was refining the translucent glazing

techniques he had been using for a number of years, creating

an effect reminiscent of Vermeer and early Rembrandt, who

had used glazing to achieve luminous qualities of depth

and resonance. As the decade progressed, Hughes concentrated

more on this aspect of work, allowing each glaze to flow

over most of the canvas before tapering off at the sides

and the bottom. In paintings like 1999/ IV (THALO DIOXAZINE),

these large areas of glazed color invite intent observation

into their depths, much as a quiet lake invites the observer's

gaze.

The

current work has taken on a renewed muscularity, as Hughes

has returned to involving more of his own personal gesture

in structuring the color. He is using brushes again, for

the first time in many years, and there is a sense that

he is working more in the paint, rather than merely

with the paint. This is not simply a return to

an earlier style, but an incorporation of the glazing techniques

of the 1990s with the more gestural brushwork that had marked

his earlier paintings of the 1980s.

An

important aspect of this new incorporation is Hughes's method

of applying the paint. Rather than using the more traditional

process of dipping the brush in the paint and then applying

it to the canvas (as he had done in the earlier work), Hughes

now pours the paint onto the canvas before working with

the brush, using the liquidity of the paint to create a

lattice-like structure of brushstrokes over the entire canvas.

Because

of the translucency of the glazing, the current works appear

much more immediately monochrome than the earlier brushed

works, in which the individual applications of paint were

more opaque and therefore more readily discernable. In 2001/

I (CADIUM RED), for example, careful observation reveals

that the apparently single hue of red is actually made of

of many layers of pigment, but unlike in the works of the

1990s, these glazes have been interwoven by the brush creating

an energetic surface texture that is enriched by the layered

depths of articulated color.

A

survey of these three decades of Hughes's painting shows

us an extraordinarily rich body of work that has been realized

within a framework of exceptional consistency. Like the

paintings themselves, Hughes's project immediately impresses

with its singleness of purpose, but upon reflection reveals

an astonishing range and complexity. Unfettered by the limiting

properties of narrative and representation, Hughes has for

thirty years been engaged in a focused exploration of the

nature of color, and through the actualized images of color

he has created we are free to participate with him in that

infinitely rewarding experience.

New

York, 2002

|

| |

EXTENDED

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baker,

Kenneth. "Galleries,"

San Francisco Chronicle, December 20, 2008.

Ashley,

Chris. "The Paintings of Joseph Hughes: Icons of Color,"

Joseph Hughes: Selected Paintings

2005-2008,

room for painting room for paper, San Francisco, 2008.

Baker,

Kenneth. "Hughes Paintings at Takada,"

San Francisco Chronicle, September 16, 2006.

Baker,

Kenneth. "Joseph Hughes at Takada,"

San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 2004.

Ashley,

Chris. "Seeing the Hovering Image: Joseph Hughes' Recent

Paintings,"

Look, See, October 2004.

Lawson,

George. "Joseph Hughes and Color Painting,"

Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002, San Francisco,

CA, 2002.

Lavino,

James. "The Image of Color,"

Joseph Hughes: Paintings 1972-2002, San Francisco,

CA, 2002.

Weinstock,

Nino. Radical Painting und Prasenz der Farbe, Richter

Verlag, Dusseldorf, 2001.

Bonetti,

David. "Berkeley Museum: Showing Off Its Assets,"

San Francisco Chronicle, March 4, 2001.

Lewallen,

Constance. "Minimalism Then and Now,"

Look (Berkeley Art Museum), Fall, 2000.

Lavino,

James. "Movement and Stillness,"

Color Based Painting, 1999.

Kokot,

Sharon. "Colors Speak for Themselves,"

Columbus Dispatch, April 11, 1999.

Schieber,

Curtis. "Radical Concrete's Rock-Solid Modernism,"

Dialogue, March/April, 1999.

Clark,

Margaret Anne. "Painting as Meditation,"

Artviews, October, 1998.

Bonetti,

David. "Taking Abstraction to Ground Zero,"

San Francisco Examiner, April 12, 1996.

Baker,

Kenneth. "Joseph Hughes at Takada,"

San Francisco Chronicle, October 21, 1993.

Bonetti,

David. "Art: At the Galleries,"

San Francisco Examiner, September 22, 1989.

Baker,

Kenneth. "Abstracts with Depth, Complexity,"

San Francisco Chronicle, September 21, 1989.

Brunson,

Jamie. "Bay Area's Response to Postmodernist Abstraction,"

Visions, Spring, 1989.

Baker,

Kenneth. "Displays of Paintings, Not Pictures,"

San Francisco Chronicle, September 19, 1988.

Anonymous.

"In Brief,"

L.A. Art Scene, July/August, 1987.

Gardner,

Colin. "The Art Galleries/La Cienega Area,"

Los Angeles Times, June 19, 1987.

Albright,

Thomas. "Joseph Hughes,"

Art in the San Francisco Bay Area: 1945-1980, 1985

Cebulski,

Frank. "Color As Perception,"

Art Week, January 22, 1983.

Albright,

Thomas. "Personal, Fresh Approaches,"

San Francisco Chronicle, January 13, 1983.

Albright,

Thomas. "Colorful Canvases,"

San Francisco Chronicle, February 27, 1982.

Albright,

Thomas. "San Francisco,"

Art News, January, 1976.

Dunham,

Judith L. "Joseph Hughes' Dual Series,"

Art Week, November 22, 1975.

Albright,

Thomas. "Catching the Art Critic Off Garde,"

San Francisco Chronicle, November 15, 1975.

Bowles,

Jerry. "Young Artists Leave Big Sur for Big Apple,"

Staten Island Advance, June 2, 1974.

Albright,

Thomas. The Way It Was: San Francisco,"

Art Gallery, October, 1972.

Allman,

Paul. "Three Artists In Their Quest for Vision,"

San Francisco Phoenix, September 13, 1972.

Fried,

Alexander. "The Lively Arts,"

San Francisco Examiner, August 17, 1972.

Albright,

Thomas. "Hughes' Studies in Colors,"

San Francisco Chronicle, August 3, 1972.

Albright,

Thomas. "Fragile Watercolor Abstractions,"

San Francisco Chronicle, August 21, 1970.

|

|